"Buy glimepiride 1 mg fast delivery, diabetes type 1 support group".

By: B. Ines, M.A.S., M.D.

Assistant Professor, Western University of Health Sciences

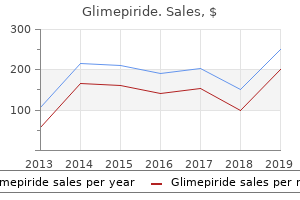

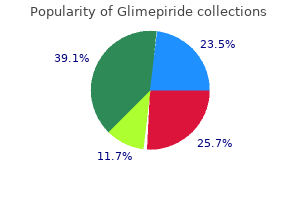

Decisions concerning formulary status of the new drug by hospitals and managed care organizations are being made diabetes insipidus blood glucose buy glimepiride in united states online. In essence type 2 diabetes qualitative research purchase glimepiride visa, health care professionals are trying to determine the place of the new drug in the context of other existing therapies signs of diabetes light headed order genuine glimepiride online. Review articles diabetes journal submission glimepiride 2mg without prescription, both traditional and systematic, follow the clinical trials, and eventually the drug will appear in textbook and monograph resources. Biological Abstracts encompasses the entire eld of life sciences and provides coverage of published biological and biomedical research including traditional areas of biology, such as botany, zoology, and microbiology, as well as experimental, clinical, and veterinary medicine, biotechnology, environmental studies, and agriculture. Interdisciplinary elds such as biochemistry, biophysics, and bioengineering are also included. International Pharmaceutical Abstracts [104], published semimonthly, is an abstracting=indexing publication which covers all pharmaceutical literature. Citations come from 4300 worldwide journals currently in 30 languages; 40 languages for older journals cited back to 1966. About 52% of current cited articles are published in the United States; nearly 86% are published in English; about 76% have English abstracts written by authors of the articles. Updated weekly, approximately 8000 completed references are added each Saturday, January through October (over 400,000 added per year). PubMed Central [105] (which encompasses Medline) is a web-based archive of journal literature for all of the life sciences. It may, at its discretion, also deposit other content such as review articles, essays, and editorials. The value of PubMed Central, in addition to its role as an archive, lies in what can be done when data from diverse sources is stored in a common format in a single repository. Links from the existing literature to other resources and databases may become part of PubMed Central. In eect, a whole article can be the subject of your search rather than a single work or index term. Available on the Internet via the Web of Science, it is updated weekly, with back-years to 1945. Even in the eighteenth century, individuals were not expected to possess all the knowledge necessary for professional life, but were expected to have the skills required to nd what was needed. Interestingly, today information management survival skills are essential to all individuals Р in both our personal and our professional lives. Although ``searching for information' is evolving to imply nding digital documents primarily using electronic search methodologies, the human as an information source remains powerful. Practitioners and scientists with like elds of interest and research form networks that function to create and share information. Experienced researchers claim they can reach any individual worldwide or retrieve needed information with only three, or at most seven, communication exchanges [107]. Physicians are frequently found to rank colleagues as their most used resource [108]. Relevance, however, is only one of several variables that establish the utility or usefulness of information. The validity of the information retrieved and the work necessary to access the information also determine the usefulness of information [109]. Steps in Conducting a Search the basic technique for a successful literature search was established years ago by Brown [113] and has remained remarkably stable despite changes in sources and technology. Enlarge the scope as necessary by adding new sources indicated by the clues that appear as the search progresses. Relevance inЇuences the usefulness of information, in that the more likely the user is to encounter the need for this particular information, the greater the relevance. Patients are primarily interested in outcomes that have personal meaning, such as morbidity, mortality, or quality of life. Information about the disease state or about surrogate endpoints has lower relevance for the patient.

As a result of the political mobilization that has occurred around many environmental issues diabetic diet example generic 3 mg glimepiride otc, the environmental justice literature has evolved through political praxis and focuses on the uneven distribution of both environmental benefits and damages to economically/politically marginalized people diabetes mellitus type 2 gangrene glimepiride 4mg low cost. Because it comes from praxis as opposed to theoretically driven academic research jamaica diabetes diet cheap glimepiride 4mg online, it provides a distinctly different context through which to understand urban human/environment interactions (see Bullard and Chavis 1993; Di Chiro 1996) diabetes type 2 vs 1 order glimepiride now. Because it is a movement rather than a research program per se, it must explicitly appeal to a broad coalition of either environmentally minded or social justice minded groups, thus promoting the widespread dissemination of the struggles endured. However, although much of the environmental justice literature is sensitive to the centrality of social, political and economic power relations in shaping process of uneven socio-ecological conditions (Wolch et al. More problematically, the environmental justice movement speaks fundamentally to a liberal and, hence, distributional perspective on justice in which justice is seen as Rawlsian fairness and associated with the allocation dynamics of environmental externalities. Cities seem to hold the promise of emancipation and freedom whilst skilfully mastering the whip of repression and domination (Merrifield and Swyngedouw 1997). Perpetual change and an ever-shifting mosaic of environmentally and socio-culturally distinct urban ecologies-varying from the manufactured and manicured landscaped gardens of gated communities and hightechnology campuses to the ecological warzones of depressed neighbourhoods with leadpainted walls and asbestos covered ceilings, waste dumps and pollutant-infested areas- still shape the choreography of a capitalist urbanization process. The environment of the city is deeply caught up in this dialectical process and environmental ideologies, practices and projects are part and parcel of this urbanization of nature process (Davis 2002). Needless to say, the above constructionist perspective considers the process of urbanization to be an integral part of the production of new environments and new natures. Such a view sees both nature and society as combined in historical-geographical production processes (see, among others, Smith 1984; 1996; 1998a; Castree 1995). From this perspective, there is no such thing as an unsustainable city in general, but rather there are a series of urban and environmental processes that negatively affect some social groups while benefiting others (see Swyngedouw and Kaika 2000). A just urban socio-environmental perspective, therefore, always needs to consider the question of who gains and who pays and to ask serious questions about the multiple power relations-and the networked and scalar geometries of these relations-through which deeply unjust socio-environmental conditions are produced and maintained. This requires sensitivity to the political-ecology of urbanization rather than invoking particular ideologies and views In the nature of cities 10 about the assumed qualities that inhere in nature itself. Before we can embark on outlining the dimensions of such an urban political-ecological enquiry, we need to consider the matter of nature in greater detail, in particular in light of the accelerating processes by which nature becomes urbanized through the deepening metabolic interactions between social and ecological processes. Urban political ecology research has begun to show that because of the underlying economic, political, and cultural processes inherent in the production of urban landscapes, urban change tends to be spatially differentiated, and highly uneven. Thus, in the context of urban environmental change, it is likely that urban areas populated by marginalized residents will bear the brunt of negative environmental change, whereas other, affluent parts of cities enjoy growth in or increased quality of environmental resources. While this is in no way new, urban political ecology is starting to contribute to a better understanding of the interconnected processes that lead to uneven urban environments. Several chapters in this book attempt to address questions of justice and inequality from a historical-materialist perspective rather than from the vantage point of the environmental justice movement and its predominantly liberal conceptions of justice. Urban political ecology attempts to tease out who gains and who loses (and in what ways), who benefits and who suffers from particular processes of socio-environmental change (Desfor and Keil 2004). Additionally, urban political ecologists try to devise ideas/plans that speak to what or who needs to be sustained and how this can be done (Cutter 1995; Gibbs 2002). In other words, environmental transformations are not independent of class, gender, ethnicity, or other power struggles. These metabolisms produce socio-environmental conditions that are both enabling, for powerful individuals and groups, and disabling, for marginalized individuals and groups. Because these relations form under and can be traced directly back to the crisis tendencies inherent to neo-liberal forms of capitalist development, the struggle against exploitative socioeconomic relations fuses necessarily together with the struggles to bring about more just urban environments (Bond 2002; Swyngedouw 2005). Processes of socio-environmental change are, therefore, never socially or ecologically neutral. This results in conditions under which particular trajectories of socio-environmental change undermine the stability of some social groups or places, while the sustainability of social groups and places elsewhere might be enhanced. In sum, the political-ecological examination of the urbanization process reveals the inherently contradictory nature of the process of socioenvironmental change and teases out the inevitable conflicts (or the displacements thereof) that infuse socio-environmental change (see Swyngedouw et al. Within this context, particular attention is paid in this book to social power relations (whether material or discursive, economic, political, and/or cultural) through which socio-environmental processes take place and to the networked connections that link socio-ecological transformations between different places. It is this nexus of power and the social actors deploying or mobilizing these power relations that ultimately decide who will have access to or control over, and who will be excluded from access to or control over, resources or other components of the environment. These power geometries shape the social and political configurations under and the urban environments in which we live. Although urban political ecology neither has, nor should have, a hermetic canon of enquiry, a number of central themes and perspectives are clearly discernible. We thought it would be useful to articulate these principles in sort of a ten-point "manifesto" for urban political ecology (see also Swyngedouw et al. Although manifestos are not really fashionable these days, they nevertheless often serve both as a good starting point for debate, refinement, and transformation, and as a platform for further research.

Despite their creativity diabetes necklace discount glimepiride 1mg visa, they do not resolve this problem so much as they sharpen an understanding of how power works through practices of reading diabetes goals discount 3mg glimepiride with amex, using diabetes hyperglycemia signs and symptoms generic 4mg glimepiride with visa, and making maps type 2 diabetes prevention journal articles purchase glimepiride. Of these approaches, participatory mapping has proven to be the most controversial. Advocates of participatory mapping have made broad claims about its potential for empowering local communities, challenging the "top-down" view found on official maps with "bottomup" perspectives on land and resources. Despite the implied creativity in approach, participatory mapping still has to adhere to certain cartographic conventions that make maps recognizable to others. Mapping is shot through with power relations that inform what can be mapped, their visual style and content defined by the forms of power and economy that they otherwise contest. Refusal to engage with mapping is no more intellectually satisfying than adhering to the status quo. Putting mapping in its place Like the history of cartography more generally, the emergence of participatory mapping is often explained in terms of technological progress. Participatory mapping was initially conceived as a method for compiling local knowledge and presenting it as data. Advocates of participatory mapping have hailed these changes as "democratizing" cartography, providing a vehicle for social change (Herlihy and Knapp 2003; Nietschmann 1995). Others have taken a more critical approach, challenging the importance of technology by focusing on how maps work with regard to power (Crampton and Krygier 2005; Crampton 2009a; Wood 2010). Often referred to as "critical cartography," this approach goes beyond questions of who makes maps and the technology used, focusing instead on the crises and problems that call for the production and use of maps. Rather than treating maps as products of exploration, critical approaches tie mapping to colonial efforts to extending authority over people and lands that remained largely unknown to colonizers. State officials and private interests followed suit, producing "official" maps to proclaim their authority (Craib 2004; Scott 1998; Wood 2010). The materiality of the world overwhelmed the ability of maps to definitively represent reality (Mitchell 2002; Turnbull 1989, 2000). People moved, rivers changed course, areas under cultivation expanded, and wars shifted boundaries. In order to work, maps had to be selective, their contents reduced to the most essential information needed to convey a pattern or perspective (Wood 2010; see also Monmonier 1996). Their incompleteness the information they omitted or excluded afforded states and other official entities the ability to bring the materiality of the world into accordance with what was shown on the map. At the same time, it created the grounds for challenging the authority of the map, to say nothing of the perspective it conveyed. Through it all, maps came to dominate understandings of the world that in turn shaped the production and use of maps. Like political ecology, the advent of participatory mapping techniques is inextricably linked to political economic factors related to the spatial dynamics of capitalism, anti-colonial movements, and environmental change in the post-Cold War era. These dynamics present a host of economic and environmental problems that define contemporary capitalism, driving the need to expand and extend markets while contending with a growing range of environmental and social crises. These crises have, in turn, marked the fracturing and fragmentation of "old" spatial categories while creating new ones. While these crises may not have created participatory mapping technologies per se, they define its applications and techniques. The goal of producing authoritative knowledge of the world remains, but their incompleteness is now less a threat to their authority than an invitation to add to it by making a "better" map. At every turn amateurs and "volunteers" overrun the idea of cartography as a profession with their eagerness to contribute new data, correct errors, and adapt maps to new problems (Crampton 2009b; Wood 2003). This endless mapping affirms their indispensability for imagining the world, to say nothing of changing it. Cultural ecology: maps as data Participatory mapping techniques pre-date political ecology. Since the colonial era administrators, military officials, and speculators relied on "native" guides to compile knowledge of the terrain, guide survey crews, and produce maps (Craib 2004; Edney 1997; Mundy 1996; Turnbull 2000; Warhus 1997). Participation was a means to an end, its messiness obscured by the neat lines drawn by expert surveyors and cartographers (Mitchell 2002; Thongchai 1994).

This section starts with antecedent fields of inquiry gene therapy cures diabetes in dogs discount glimepiride 2 mg visa, followed by implicit and explicit historical connections diabetes mellitus awareness questionnaire order discount glimepiride online, and then moves toward recent patterns of research diabetes type 2 zonder medicatie cheap 4 mg glimepiride with mastercard. Some common antecedents Political ecology and hazards research share at least three interesting antecedents diabetes treatment centers cheap glimepiride 4 mg on line. Cultural ecology is perhaps the closest antecedent field in time and substance, as it focuses on subsistence strategies as the "core" around which issues of risk, scarcity, and adaptation revolve (Zimmerer 2006). Hazards research and cultural ecology actually developed concurrently and to some extent perhaps in dialogue with one another (Turner 2008). A thorough review of the historical links between political science, political geography, hazards, and political ecology is warranted. In the early twentieth century, the field of resource geography provided a broad platform for human ecology and hazards research. The mid-twentieth century witnessed a strong renewal of natural resources research at institutions like Resources for the Future, although that research agenda was framed in terms of applied microeconomics, in contrast with the more strongly political and Marxian strands of critical resource and hazards geography. The reframing of hazards research and emergence of political ecology In historical terms, hazards research began with an agenda of progressive reform in the pragmatist sense of the term from the 1940s onward (Robbins 2011; Wescoat 1992). White explained how the construction of levees reduced flood risk perception in ways that induced increased floodplain occupance, investment, and long-term losses. He argued consistently over a half-century that while extreme events are natural ("acts of God"), hazards losses were "acts of man" (White 1945, p. In the meantime, however, hazards research came under heated criticism as atheoretical, as uncritically accepting the politics of vulnerability, as overemphasizing the power of science and technology, and having an inadequate framework for explaining processes of social change. As there was little political ecology per se at that point, the main lines of criticism came from human ecology and Marxist political economy, though many of these critics and their students would become leaders in political ecology. While these criticisms triggered new lines of research, they also included some biases. Research on risk perception, behavior, and communication were proscribed as "scientism" 296 Risk, hazards, vulnerability, and capacities (Waddell 1977). Research on environmental and resource economics that advances the ideas and methods of neoclassical or applied welfare economics receives less attention in political ecology, as compared with radical political economic approaches. Nevertheless, at least three profound lines of research have emerged from these critiques: · · · vulnerability research social power relations politics of resource access and conflict. Hazards researchers as well as their critics have turned their attention to these issues. Political ecology offered new approaches for addressing vulnerability, inequality, and the politics of hazards; but it is not clear whether the two fields were developing in dialogue or in parallel with one another. The next section shows that the linkages to date have been limited with perhaps slightly more attention to political ecology by hazards researchers than vice versa (cf. A review of recent research A systematic bibliographic search was conducted to assess the relationships between political ecology and various aspects of hazards research (for "bibliographic mapping" methods see Collaboration for Environmental Evidence 2013; Wescoat 2014). Results were screened for relevance, mainly by confirming whether the keywords were used as research terms or as ordinary language (the latter were excluded). In cases where more than one hundred hits were returned from a keyword search, the term was re-entered as a title word. First, "risk" is the keyword most frequently associated with political ecology, which reflects its use across many disciplines. Subsequently hazards research shifted toward studies of "resilience" to re-balance the emphasis on structural inequalities suffered by victims 297 J. By comparison, political ecology citations still appear to focus more on vulnerability than resilience (Miller et al. One surprising search result was the high frequency of research on the political ecology of hazards in doctoral dissertations. Eight of the ten books on political ecology and vulnerability identified in WorldCat were theses or dissertations. Interestingly, as in earlier generations the most frequent research topic involves water-related hazards. Interestingly, few dissertation writers continued to write about the political ecology of hazards in subsequent journal articles. Pelling (1997, 1999) is an important exception whose doctoral research led to book chapters and articles on the political ecology of flood hazards in peri-urban Georgetown, Guyana. It shifted from agrarian toward urbanizing environments, and toward local community development rather than government institutions. This observation should not be exaggerated as leading critical water hazards researchers employ ideas and methods associated with political ecology.

Buy cheap glimepiride line. Dairy Gives You Diabetes?! Tom Hanks & Nick Jonas (Type 1 and 2).